Around the world, people and small businesses are working and selling in new ways, using digital platforms. News reports, heated policy debates, and our daily interactions with drivers, delivery people, freelancers, innkeepers, and virtual e-commerce storefronts all underscore a growing awareness that there is something essential and different about finding one’s way and earning a living in the platform economy.

This page details our approach to “platform livelihoods,” an umbrella term (or lens) we use to connect the broad structural transformations associated with the rise of platforms to the experiences, challenges, and opportunities facing workers, entrepreneurs, and the self-employed. This approach intentionally draws on several elemental activities to join and cross-pollinate between distinct debates in the digital development literature about gig work, e-commerce, the sharing economy, and the attention economy, for while each of these new “economies” is different, they each have platformization at its core.

A broad definition of "platform livelihoods"

In our view, platform livelihoods are the ways people earn a living by working, trading, renting, or engaging in digital marketplaces

It’s an intentionally broad concept, and many terms work together to create it:

The term “platform” is common in industry and specialized discussions about the digital economy. There are many typologies of platforms available, but at the broadest level, Cusumano, Gawer, and Yoffe (2019) make a useful distinction between (a) innovation platforms — software (like an operating system or suite) that runs other third-party software and (b) marketplace platforms — digital hosts, usually businesses themselves, that connect buyers and sellers of goods, services, or labor in two-sided or multi-sided markets. Social media platforms can be understood as either (2a) a special kind of marketplace platform or as (c) a close cousin — monetizing attention to user-created or creative content via advertisements.

Platformization is powerful and increasingly common, but never neutral. With the platformization of almost every kind of market (including labor markets) comes new “logics” — new structures, rules, incentives, and pressures. Platformization makes new winners and losers, scrambles value chains, and alters age-old relationships among labor, capital, and the state. For the digital development discussion, we are more interested in marketplace and social media platforms, as shown in our approach’s emphasis on “digital marketplaces.”

“Livelihoods” draws on a broader discussion in the development literature. As a concept, it is broader, more fluid, and more flexible than “jobs” or even “work.” “Livelihoods” better encompasses part-time, casual, and informal work, and is sensitive to combinatory practices in which several activities and skills are necessary for survival. Rather than emphasizing a specific role or job title, livelihoods involve making a living as a set of strategies to combine assets, capabilities, labor, and social resources.

Here’s how “platforms” and “livelihoods” connect: when combined, they refer to more than gig work. The broad umbrella of “platform livelihoods” suggests that there are many ways to earn a living and many ways in which platforms are becoming involved. To convey this heterogeneity, we’ve settled on a view which focuses on a few elemental livelihood activities — on what people do — rather than on what platforms provide. These are working, selling, renting, and engaging.

- Working links most closely to “gig work” and is perhaps the most prominent and hotly debated example of platform livelihoods. Individuals rely on platforms to match their labor to compensation outside the contexts (and any protections) of employer-employee relationships.

- Trading maps onto e-commerce and social commerce. Individuals or small enterprises offer products and services to customers via marketplace platforms and/or social media. Almost every microenterprise involves trading — wholesalers, retailers, manufacturers, service providers, and even artisans and artists can sell their products and services via platforms small and large.

- Renting is the monetization of assets via a platform. Lending or leasing a tractor or truck by the hour or day, or offering a room of one’s house on Airbnb all fall under this kind of asset utilization, as does lending (renting) money on peer-to-peer loan platforms.

- Engaging has, literally, captured the online world’s attention: Instagram influencers, YouTube and TikTok content creators, even affiliate marketers getting commissions for well-placed clickable ads. All of these can be seen as engaged in platform livelihoods, too. The key element distinguishing this platform livelihood activity from the others is that it involves at least three parties besides the platform: the creators, the audience, and the advertisers. Through a remarkable, though often problematic, combination of platform design, scale, algorithmic weighting, and (often) targeting data, the result is an “attention economy,” in which engagers can prosper by being compensated for bringing attention to content (and/or to the ads alongside that content).

This view of “many livelihoods” touches almost every sector of the economy. Indeed, many familiar roles are actually combinations of these activities. Take, for example, the ride-hailing driver who owns their car, drives nine hours a day via two different platforms, and rents their vehicle to another driver in the evenings. Their efforts are better understood as a combination of renting (assets) and working (labor) rather than as the application of labor alone. In this view, it is best to avoid assuming that people are exclusively renters or traders or engagers; instead, many will combine these practices in distinct ways to pursue their distinct livelihoods.

We situate these activities “in” instead of “by,” “via,” or “for” platform marketplaces. These platforms aren’t merely tools that workers and sellers can use, but structures they must navigate. Nor are these individuals engaged in activities “for” the platforms as employees or agents; individuals and small firms operate without employer-employee contracts. For now, “in” best describes how individuals pursue livelihoods within the contexts (affordances and constraints) at least partially established by platforms.

From this definition, and drawing on a detailed literature review of 75 studies of platform livelihoods in the global South, this framework addresses three broad questions for the digital development community:

What are the experiences of people with platform livelihoods?

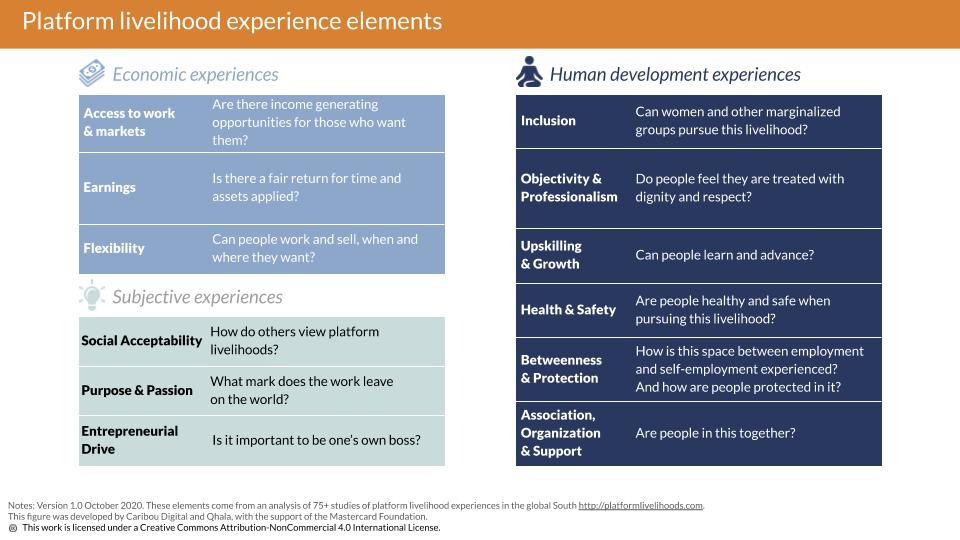

We identify twelve elements—the kinds of experiences that individuals share and value when discussing their livelihoods with friends, family, and even the occasional researcher. They are a mix of economic, subjective, and broader human development experiences.

What are similarities and differences between platform livelihood types?

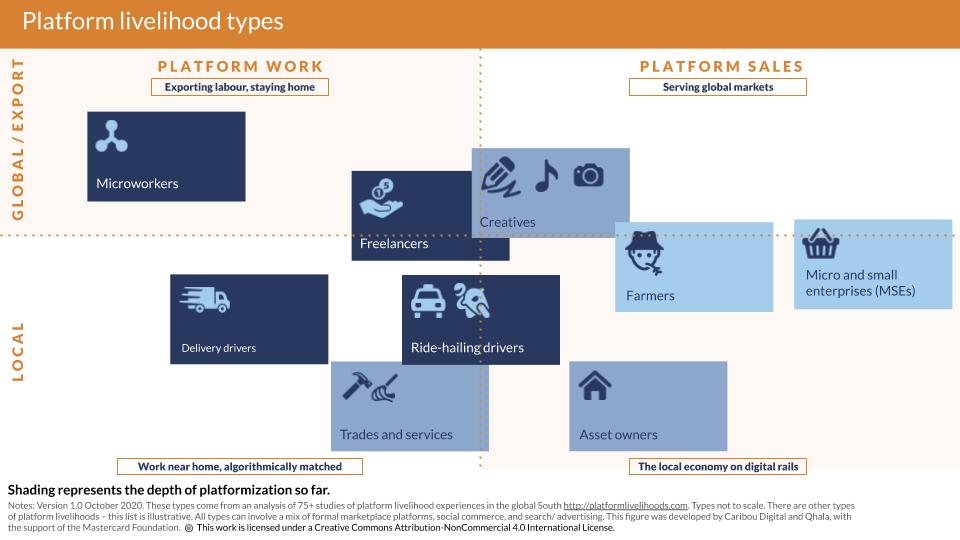

We offer a landscape of nine illustrative types of platform livelihood. Note that these are roles that individuals or small enterprises can fill, rather than “business models” or the names of specific platforms.

These are not the only roles that platforms are transforming or enabling, but these nine represent enough of the diversity in platform livelihoods to make two key distinctions. These types mix local and global (digital only) markets. Some of these roles are for individuals seeking work and offering their labor. Some of these roles are for small enterprises and even small farms, looking for new sales channels and new ways to connect with markets.

The early research and policy literature has been concentrated in platform work, especially ride-hailing, freelancing, and microwork, but in the longer run, platform sales (whether via marketplaces, social commerce, or search and discovery) may end up altering the livelihoods of a greater number of people around the world.

What kinds of technologies and business models support platform livelihoods?

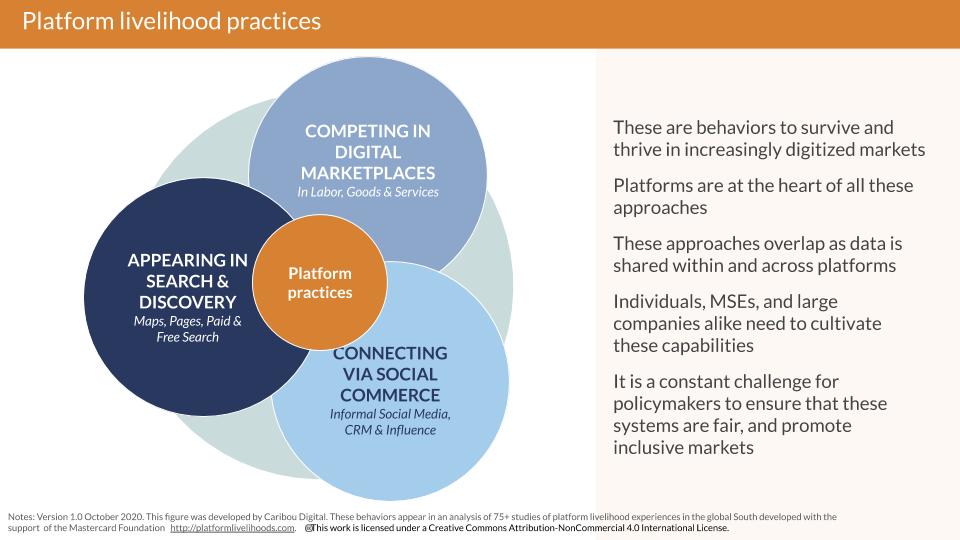

Individuals and small enterprises use a mix of platform services and approaches to pursue their livelihoods.

- The most easily recognizable way via formal digital marketplaces —the formal “multi-sided markets” in labor, goods and services, though with individuals and small firms can find customers.

- Informal social commerce—selling goods, services and even ‘influence’ via personal Facebook pages, Instagram, WhatsApp, etc. is also growing in popularity and impact, even if the research literature here is still sparse.

- And there is often (still), search and discovery. Millions of small businesses pay for advertising on Facebook and Google and other social media platforms, Many work to refine how they appear on maps or other digital databases and apps. Some have websites or social media pages or storefronts of their own. These activities, too, support platform livelihoods.

These activities and services blur and intersect as digital platforms continually slice and recombine, mediating the connections between sellers and their markets in ever-changing ways.

One the one hand, the digitalization and platformization of economies seems to reward sellers and workers who have developed capabilities in more or more of these than one approaches.

On the other hand, it is simultaneously a critical matter for inclusive digital development policy that these mediated connections do not divide, dissuade, or discriminate against small scale sellers and the self-employed.

In the longer run, we may update the online evidence map and accompanying discussion with a per-technology filter to better reflect differences and similarities (in practice and in policy) across these technological approaches.

How to use this framework

There are many organizations and researchers involved in studying and building policy around the activities this post calls “platform livelihoods.” The community of practice is broad, as are its perspectives and frames.

Our goal with the lens of “platform livelihoods” isn’t to refute or diminish the existing frames and debates about gig work, e-commerce, or any other element of an increasingly platformed economy, but rather to bring together disparate parts of this arena, to spark conversations and share knowledge. Therefore, we hope the concept is useful to you.

By providing a common language framework and a map of several kinds of platform livelihoods, this framework can help uncover many trends and cross cutting issues. For example, in this first iteration of the literature review we used the framework to explore four durable themes: gender, rurality, youth, and COVID-19. We also outline four emergent dynamics worthy of scrutiny: fractional work, amplification, hidden hierarchies, and contestation.

We hope that you might and use this framework in your own research, design, or policymaking activities. All the materials in this framework are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International. We ask only that you provide attribution if this turns out to be useful to your research.

The platform livelihoods framework was developed in collaboration with Qhala, with the support of Mastercard Foundation